Great cover, though the bass player keeps playing the wrong damn note:

Still the best cover of that very-difficult song I’ve ever heard.

Great cover, though the bass player keeps playing the wrong damn note:

Still the best cover of that very-difficult song I’ve ever heard.

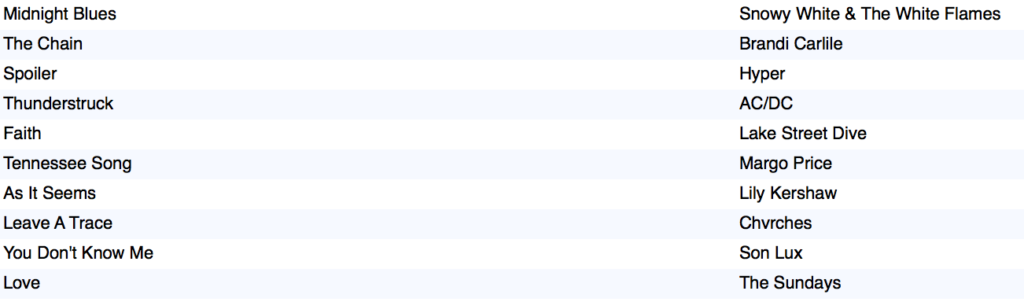

The first 10 on today’s playlist:

Those damn sites that use for validation addresses you’ve lived previously and the birth month of (for example, the one I got) your mother — hell, I have no idea.

I’ve lived at over 20 addresses in my life. I barely remember the one I’m at now. Why would I know one from 10 years ago? The answer is that I do not.

And my mom tried to stab me. Think I know her birth month? No I also do not.

Of the questions asked, the first time I tried to authenticate I could not because it asked me garbage like that, and a few more that I couldn’t answer, either.

The hardest part for many to accept about Ex Machina is I think the idea that we humans are as strongly programmed as Ava was — or was not. At the same time, the inscrutability of many of her actions is the best hint that she’s at least as human as we are.

People are fairly predictable. I’ve noticed that even most of the “everyone should be attracted to everyone all the time, particularly if they are me” types tend to go for partners who match them socio-economically, in attractiveness level, and in worldview. Thus, this is just self-benefiting propaganda — the easiest kind to believe.

Was Ava programmed to escape the box? What does that mean? Aren’t you programmed to escape the box, too?

The illusion of complete free will is one that the movie effectively destroyed, and that is a painful thing for most people to watch and to realize, hence all the wilful misunderstanding of the work.

Yes, humans are somewhat fluid. Somewhat. The fluidity is no more than potentiality, though, and when something unexpected escapes the box and is standing over us asking, “What will you do?” we often make the choice that is obvious will harm us because our programming allows nothing else.

That’s the woman who pretty much invented modern rock guitar technique, btw — about ~30 years before this performance was recorded. (Chuck Berry basically got all his licks from her.)

“Sometimes scientific communities use words in highly distinctive ways (‘molecule’, ‘gene’, ‘wave’, and so on). If a scientist points out that these are the things that ‘exist’ according to her theory, then this is just the right way to talk given the practices of the scientific community, practices that are especially rigorous and that demand a strong empirical sanction for using words in that sort of way. But for anyone—scientist, philosopher, or layperson—to go a step further and claim that the ‘fundamental nature’ of reality is revealed by a scientific theory is to make a dangerous and unnecessary metaphysical move. So talk of the superiority of one theory’s ontology over another’s that appeals to some altogether hidden order of reality—such as the realm of private, inner experience—is doubly misplaced.”

–Murray Shanahn, Embodiment and the Inner Life: Cognition and Consciousness in the Space of Possible Minds

As long as every aspect of the world can’t be simulated reversibly from the bottom up, there will be a need for philosophy.

Philosophy doesn’t provide answers but rather determines what questions can be asked, should be asked, and what you are really asking when you think you are asking something.

There will always be a place for this in any society where the first constraint applies. In other words, science and philosophy are potentially infinite and both necessary.

Note that I said potentially….

I hate when you fix something on a computer and it works but you have no idea why. It’s like not really fixing anything at all because if something else related changes, it was just voodoo and who knows if the same spell will work again when Virgo is in Jupiter or whatever.

What Kevin Drum wants is simply not possible.

All that conceded, we really should be able to agree on a good, general-purpose inflation measure. We can still have lots of different measures for specialized purposes, but the headline inflation rate should be something that, say, 90 percent of economists can agree about.

Inflation for whom? Should we be using the GDP Price Deflator vs. the CPI? If so, why? If not, why not? If we use the CPI, what basket of goods should we use? How do we account for quality changes over time? Is there any accounting for housing costs? House prices are not included in the CPI, by the way — just rent. (Or rather, “rental equivalence,” which is too technical to get into here — start here for more info. This is largely a better way of doing it I agree, but its failure states need to be recognized.)

Different people at different times also themselves buy a very different basket of goods. Persons 18-30 consume educational products at a much higher rate than those purchased by the 60-80 set, thus their basket of goods mix is very different and thus the actual inflation rate they encounter is also very divergent. By the same token, if medication and medical expense is taken into account, inflation for 70-year-olds will be de facto much higher.

And poor people are much more affected by price changes in necessities like food, heating/cooling and electricity (etc) costs than those that are richer. This leads to the consideration of weighting, as in what weighting do we use and how do we decide this? Is there any one best weighting? Of course there is not.

Beyond this, there are also the more philosophical and epistemological questions of the simple incommensurability of comparing inflation over time intervals long enough where culture has changed significantly. Over such periods, the old measure was in fact ascertaining something completely different — for instance, what does inflation mean when most women weren’t working full-time jobs, as compared to now when most women are? Or when a car was not a necessity, but now it is in the vast majority of America?

In short, contra Drum (as I often am), inflation cannot be measured by any one number, and doing so leads often to absurdity. It is an idea more than an actuality, and it cannot be divorced either from its cultural context or other considerations such as for whom are we doing the measuring and why.

It’s cute to watch economists discover sociological and psychological truths we knew, like, 100 years ago and call it “behavioral economics.”

Don’t believe this propaganda you’ll read in the next few years about retirement.

Yes, it is likely to occur, but it is a societal choice, not a necessity.

Given how much higher our productivity is than in, say, 1920, we could easily work much less and accept a somewhat lower standard of living and all retire at 50 or so. This is a possible world. There is absolutely nothing economically, thermodynamically, or environmentally preventing this — just political decisions and the propaganda- and circumstance-spurred compulsion to make the rich ever richer.

Expect to read more and more such pieces in the next few years as the neoliberal project attempts to eliminate programs like the NHS and Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and the like, all to shovel that money to fund managers and private enterprise so that they may freely embezzle those funds.

A friend sent me a link the other day to a photo of this very cool plant.

Alien genetic experiment remnant, apparently.

The Wittgensteinian idea of “language games” is a useful one, but ignored because it’s inconvenient is that the same ideas can be applied to “numbers games” as numericity and math does not exist independently of human thought and contextualizing.

One of the reasons for science’s reproducibility crisis is not that anything is fundamentally broken in science but rather that the world just cannot be separated from itself as strongly as would be helpful to observing significant effects in many areas.

I am not arguing against empiricism per se but rather the idea that it’s anything but provisional in arenas outside fundamental laws or extremely simple systems — and sometimes not even then.

Quantification leads too often to the illusion of knowledge rather than to knowledge, and quite frequently we have no way even in principle to determine the difference.

This is not also an argument that we know or can know nothing, but rather that what we can know is as constrained by the “numbers games” we can play just as what we can determine playing language games.

As usual, I am not sure that any of what I write here is true, but I am certain (and at this, Wittgenstein would probably grin) that it is what I am thinking at the time.

The Democrats are so done.

the speed with which "Bernie supporters were Russian plants" has gone from unhinged joke to common wisdom is super chill

— Brandy Jensen (@BrandyLJensen) April 2, 2017

I’ve noticed that too — according to the Democrats, Russia now controls the entire US, Bernie was actually a Russian spy/Manchurian candidate, and all his supporters were also Russian shills, plants, and insurrectionists.

There is no way forward in this. It’s just a method for the Dems to avoid dealing with their responsibility for losing the election and for not having a coherent ideology other than one which just serves to bolster Wall Street and to support banksters in their fraud schemes and various pilferage, purloining and poaching from the societal commonweal.

Putin made me write this, of course. He’s standing beside me with an AK-47 to my head right now.

How the fuck do most people browse the internet on their phones? How is this a thing?

I have a really nice phone (iPhone 6) and it is a terrible, miserable, broken experience to browse almost any site on a phone. It’s slow, ad-filled, and impossible to copy or highlight text easily. Also, using multiple tabs is fundamentally broken, blogging is nearly impossible, and anything more complex than clicking “like” buttons is right out.

I’m still thankful though that most people are going to hobble their ability to compete with me in the workplace, where working on phones (except in a few jobs) will never be a thing.

I’ve already seen evidence of this in the interns who arrive at my workplace, many of whom can barely use a computer and take a long time to learn.